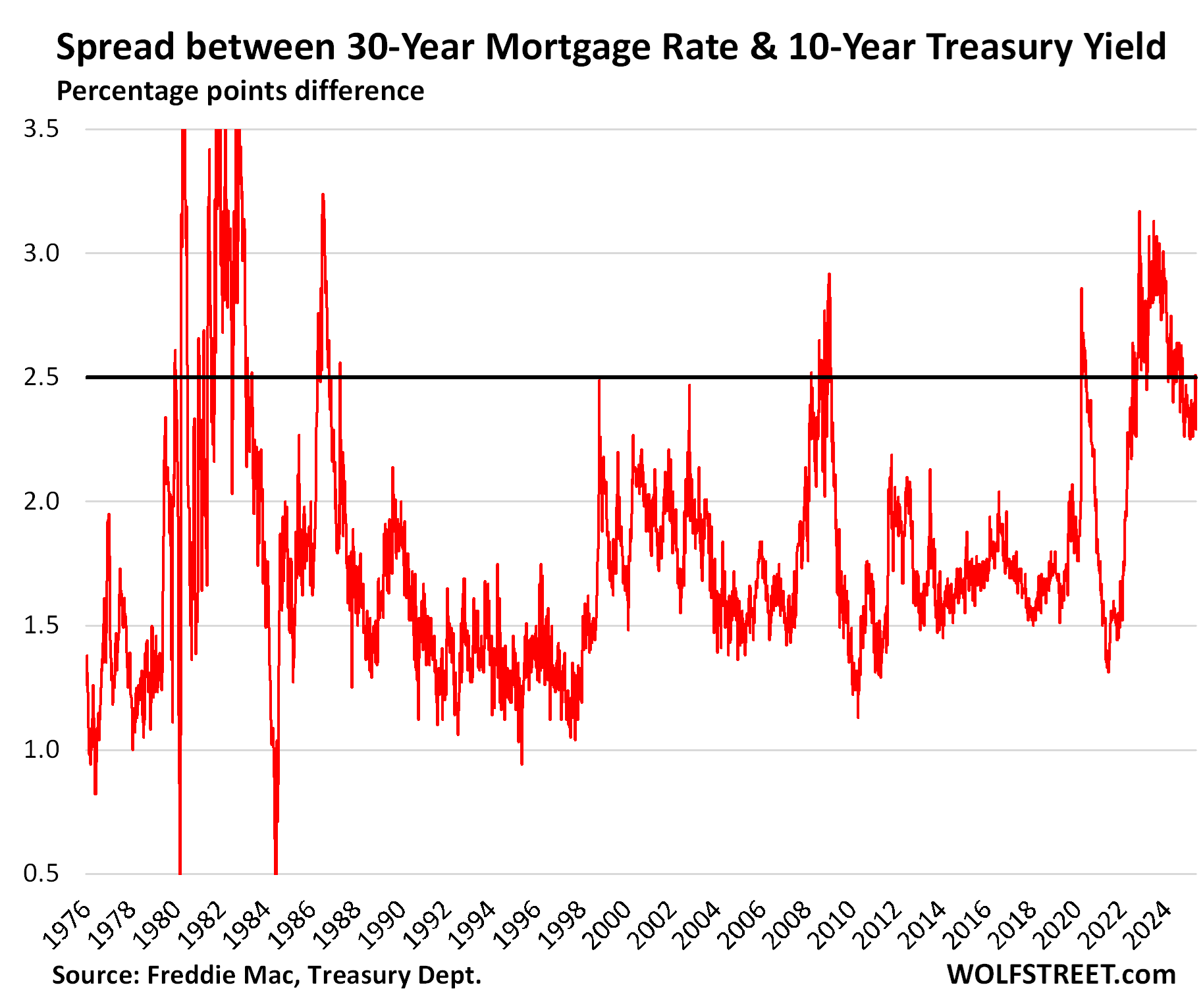

Mortgage rates are higher in relationship to the 10-year Treasury yield than they were most of the time over the past 50 years. There are reasons.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

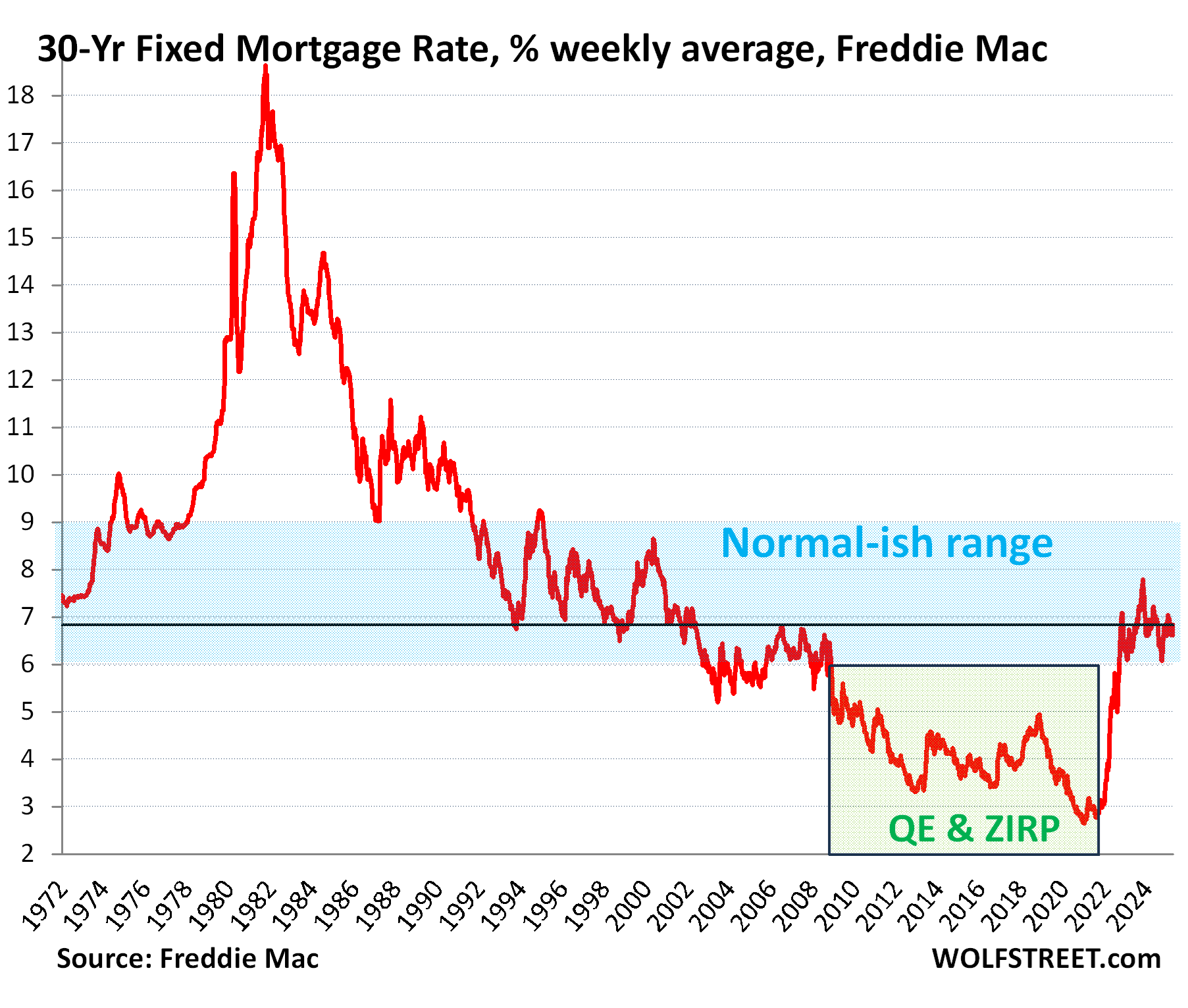

The 30-year fixed mortgage rate tracks the 10-year Treasury yield but is higher. The amount by which it is higher – the spread – varies substantially. When the Fed bought mortgage-backed securities during QE, the purpose was to narrow the spread and thereby repress mortgage rates, and eventually they fell below 3%. Then the Fed started shedding these MBS during QT in mid-2022 and stepped away from the mortgage market entirely. Mortgage rates rose faster than the 10-year Treasury yield, and the spread widened substantially, shooting past 3.0 percentage points, the widest since 1986, but then started to narrow again.

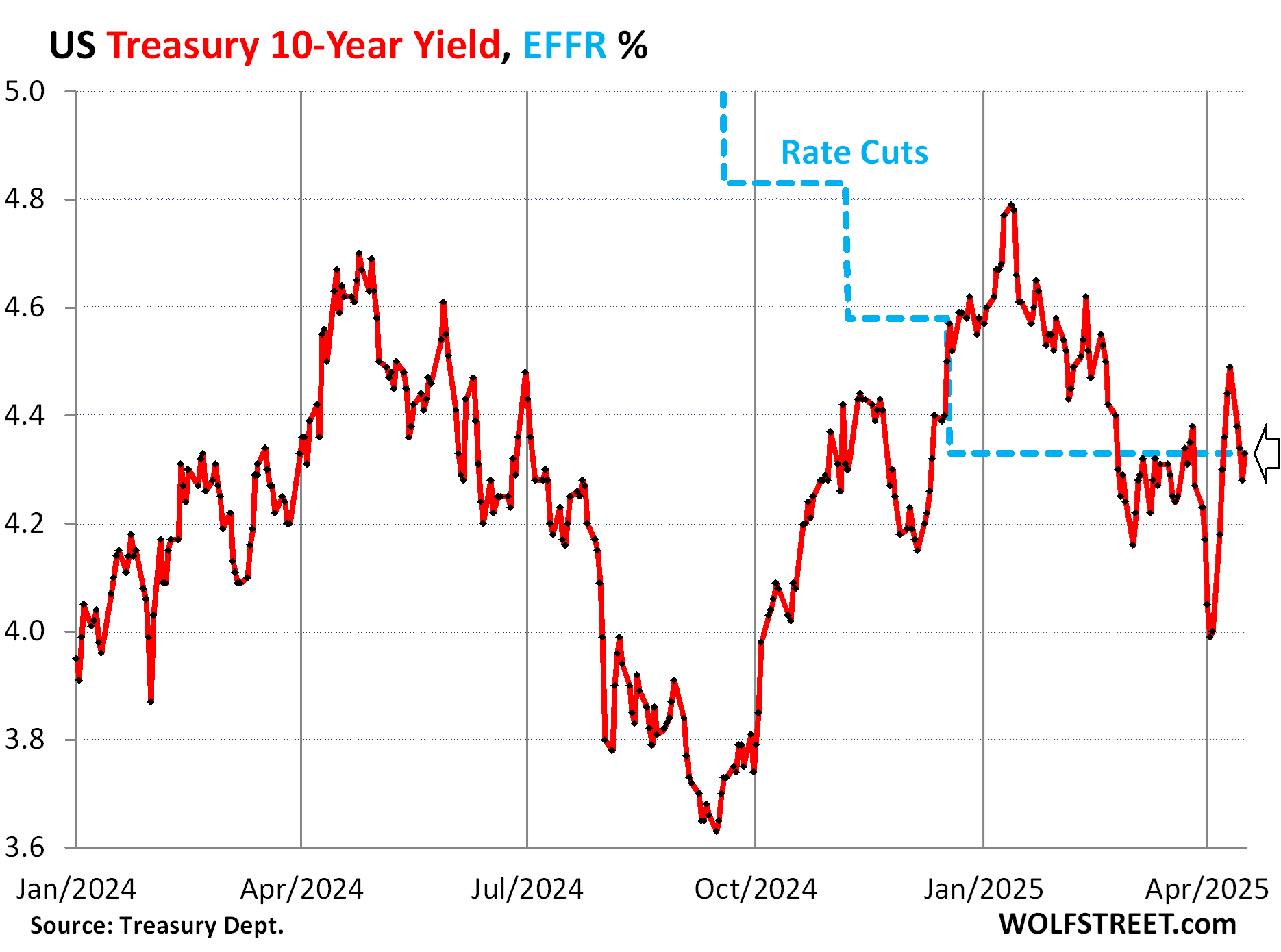

But that narrowing process hiccupped. The average 30-year fixed mortgage rate rose to 6.83% per Freddie Mac’s weekly measure on Thursday, but the 10-year Treasury yield was at 4.33%, and the spread between them widened to 2.50 percentage points, the most since September 2024. Over the past five decades, there were not many years when the spread was this wide.

The 10-year Treasury yield has undergone some drama in recent weeks. It plunged from 4.77% on January 10 to 3.99% on April 3, including a 40-basis point plunge in the few days before April 3, and then the yield bounced back in a near-symmetrical manner, and on Thursday it settled at 4.33%, exactly where the effective federal funds rate (EFFR) is, which the Fed targets with its monetary policy rates.

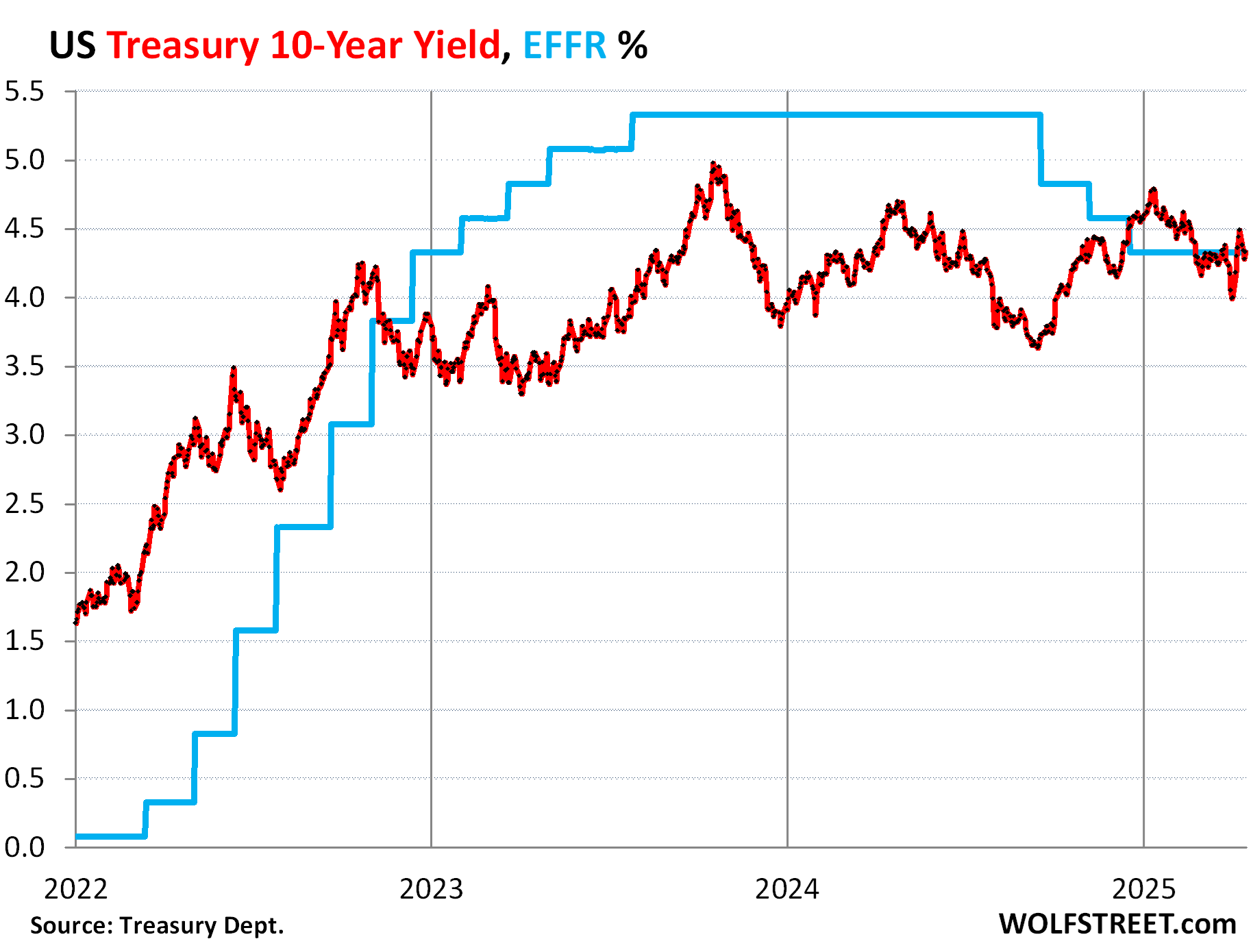

The bond market got frazzled by the Fed’s 100-basis-points in rate cuts in late 2024 while inflation was re-accelerating, which triggered a bond selloff in late 2024 through early January, that had caused the 10-year yield to spike by 114 basis points from mid-September through mid-January, even as the Fed cut by 100 basis points. This taught the Fed – but not Trump – a lesson!

The Treasury market fears inflation more than anything, and it wants to be compensated for this expected future inflation by demanding higher yields. When it comes to inflation fears, the Treasury market is not to be trifled with.

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has been trying to manipulate down long-term Treasury yields to make funding in the economy for businesses and households less costly. His efforts have been fortified by the Fed’s more hawkish stance on inflation (the wait-and-see policy), which reduced the bond market’s inflation fears. Yields then declined in 2025 until they plunged too far and bounced back and now settled at 4.33%. But in a three-year view, the drama was just a blip:

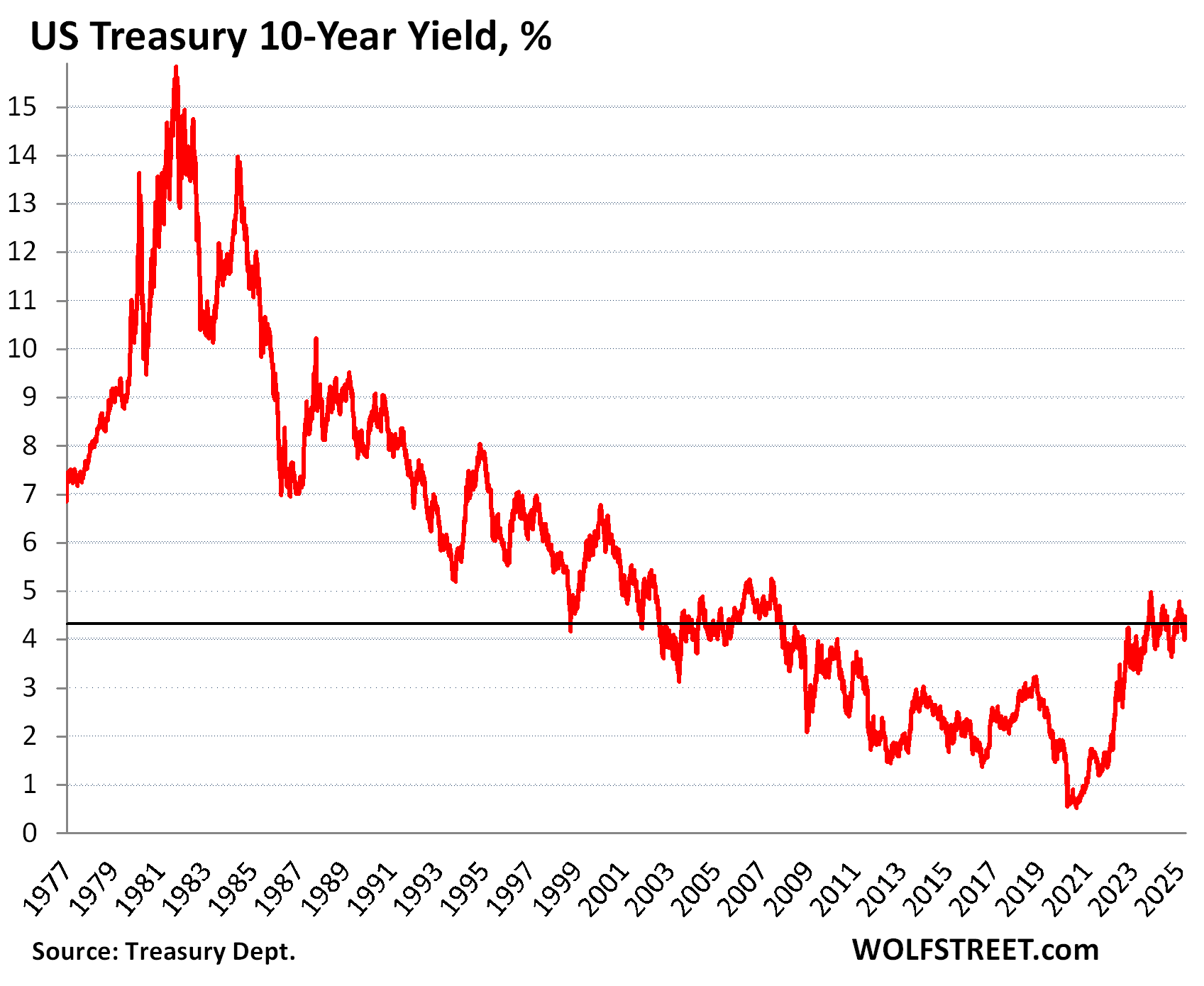

During the 40-year bond bull-market, the 10-year Treasury yield zigzagged down from 16% in 1981 to 0.5% in mid-2021. When yields fall, bond prices rise, and a good time was had by all, but it’s over. It was followed by raging inflation in 2021 and 2022. While inflation has cooled from those levels, it continues to fester, and it started re-accelerating last fall. When bond market investors see and expect higher inflation over the term of what they’re buying, they demand higher yields to be compensated for it.

The average 30-year fixed mortgage rate rose to 6.83% (Freddie Mac). It has been above 6% since September 2022.

Historically, the average 30-year fixed mortgage rate didn’t drop to 5% until the Fed started QE in 2009, which included the purchases of massive amounts of MBS, which helped push down mortgage rates and was part of the Fed’s scheme of interest-rate repression and asset-price inflation. But then raging inflation broke out in 2021 and put an end to it.

The Fed and the spread. After shedding $2.24 trillion from its balance sheet through QT, the Fed has now slowed the pace of QT. But it has not slowed the pace of QT for MBS, only for Treasury securities. And that’s a key here.

MBS come off the balance sheet mostly through passthrough principal payments as mortgage payoffs (sales or refis) and principal portions of mortgage payments are forwarded to the holders of MBS, such as the Fed.

These passthrough principal payments have been running at about $15 billion a month for the past year. If mortgage rates drop a lot, the pace would speed up. The Fed has said many times in its official announcements that it plans to get rid of all its MBS. It stepped away from the MBS market in September 2022, and that market has been on its own ever since, unleashed from the Fed’s controlling fist.

Before QT started, the Fed held $2.74 trillion in MBS. QT has whittled that down to $2.19 trillion, and whatever comes off via passthrough principal payments comes off and goodbye.

But the Fed further slowed the pace of the Treasury securities roll-off to just $5 billion a month, starting in April. The Fed then reinvests the amounts that mature in excess of $5 billion a month by buying equivalent Treasury securities at Treasury auctions. So the Fed is again with both feet in the Treasury market, replacing a big part of its maturing securities with new securities.

And this asymmetry of leaving MBS yields, and thereby mortgage rates, entirely up to the market, while still meddling in the Treasury market has increased the spread between the 10-year Treasury yield and mortgage rates.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

Energy News Beat