By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

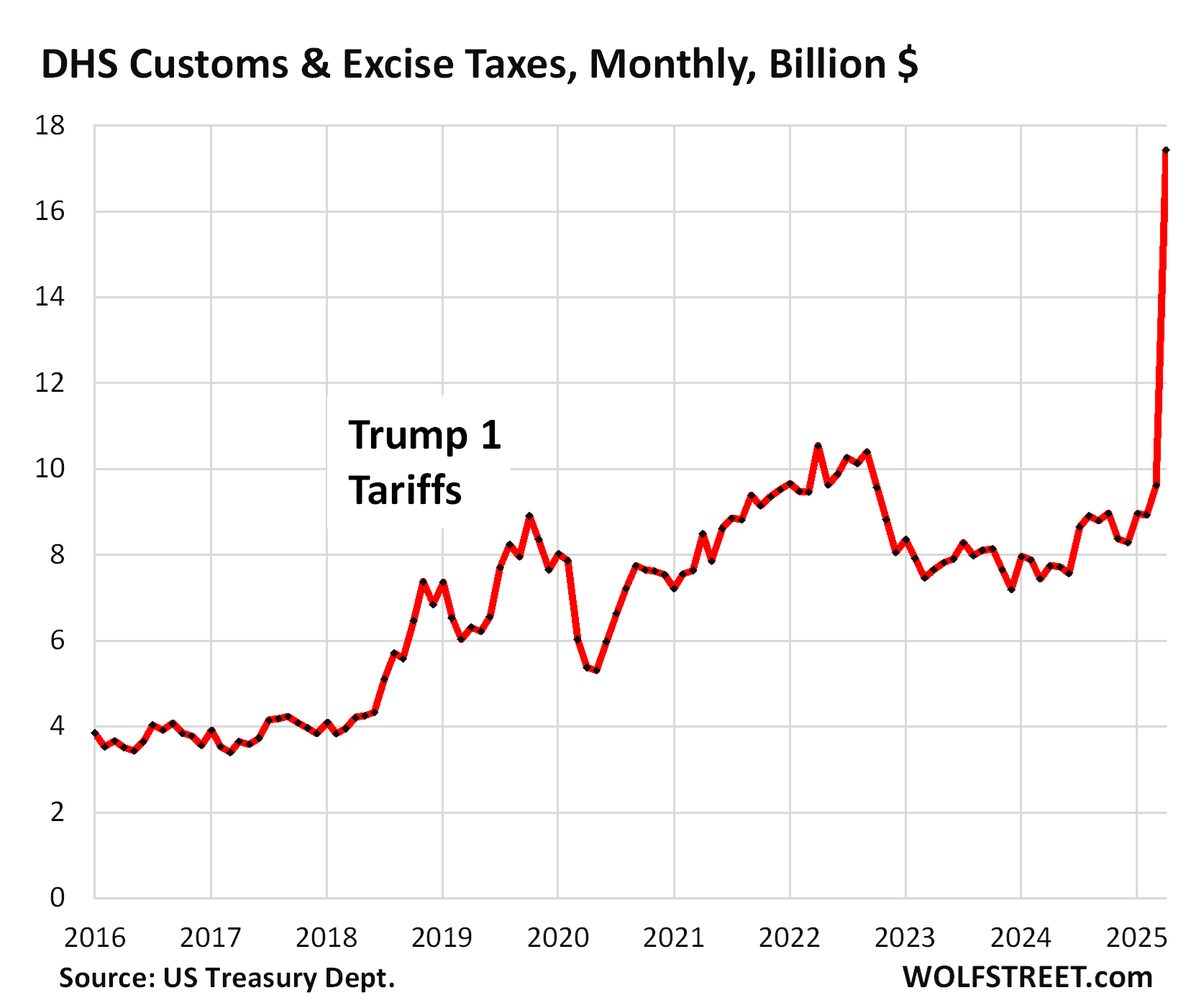

Collections from customs and excise taxes spiked by 81% in April from March, to $17.4 billion, more than double the average monthly collections in 2023 and 2024, according to Treasury Department data today.

And in March, collections from customs and excise taxes ($9.6 billion) had already increased by $1 billion from February ($8.9 billion). Over those two months, collections nearly doubled (+95%).

This $17.4 billion is the amount in customs and excise taxes that the Department of Homeland Security – which includes the law enforcement agency Customs and Border Protection – transferred in April into Treasury’s checking account at the Fed, the Treasury General Account.

A chart like this is kind of funny. But it shows that something substantive is happening. Tariffs are taxes paid by businesses. How much? It’s adds up:

For example, GM just announced that the new tariffs would cost it $4 billion to $5 billion this year and lowered its earnings forecast with respect to that. It has also begun to shift production to the US to dodge some of those tariffs.

GM manufactures components in China, it manufactures its Buick Envision at its joint venture in China and imports it, it imports vehicles and components from Mexico and Canada, it imports components and materials from around the world. After its bailout out of bankruptcy by the US government in 2009, GM focused on China and Mexico and shed dozens of US production facilities for components and vehicles. So now there’s a price to pay.

GM cannot pass on the tariffs to consumers because automakers are having to discount their models and throw incentives at the market to sell their vehicles so that they can keep their production lines going. After the massive price hikes during the pandemic, there is no more room left to hike prices. Consumers have had it.

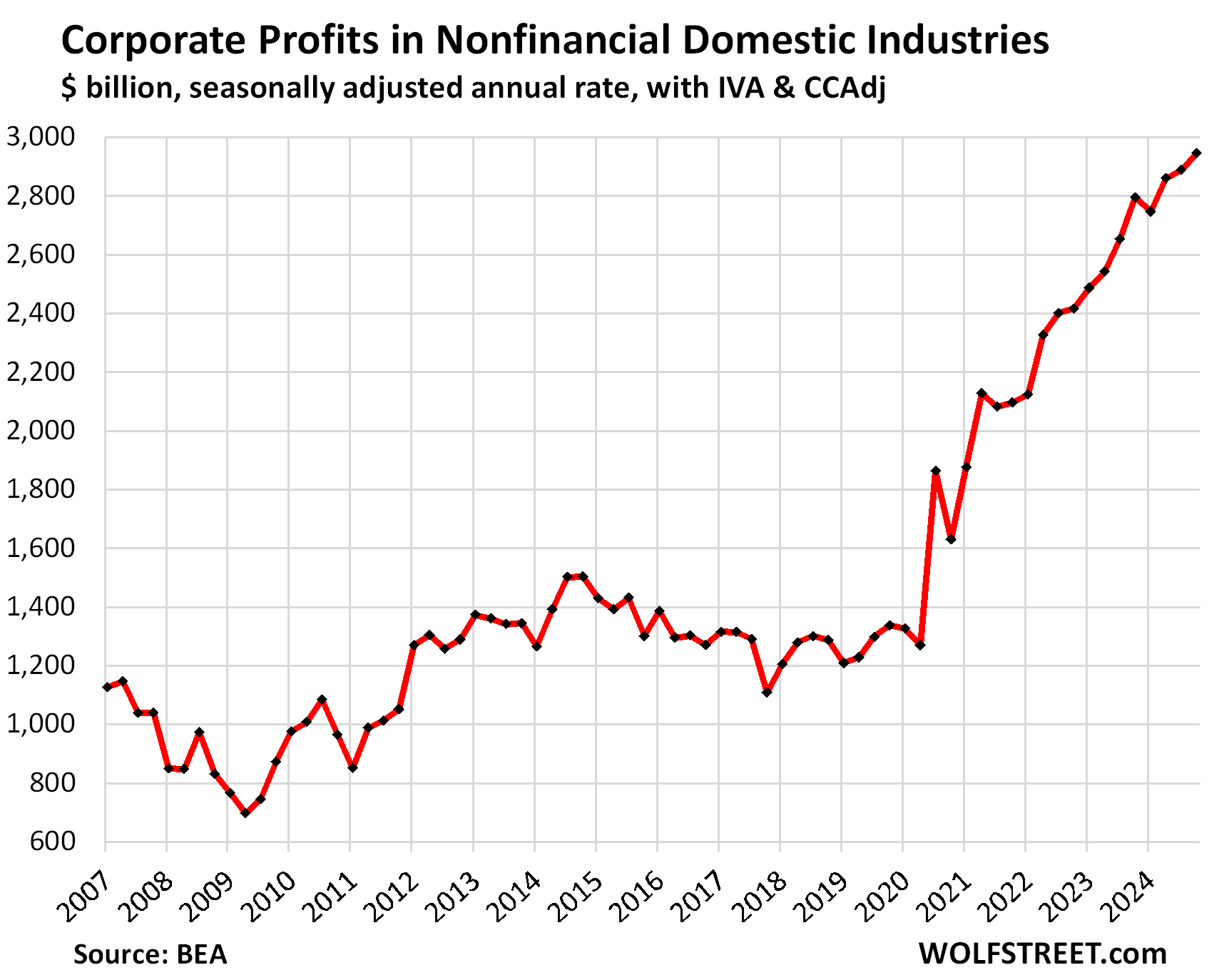

But profit margins in the auto industry have been huge following those massive price hikes, and the companies can eat those tariffs, show up with lower profits, and still be fine. See GM.

And not just in the auto industry. Nonfinancial companies in the US made out like bandits during the era of massive price increases — and they have plenty of room to eat the tariffs:

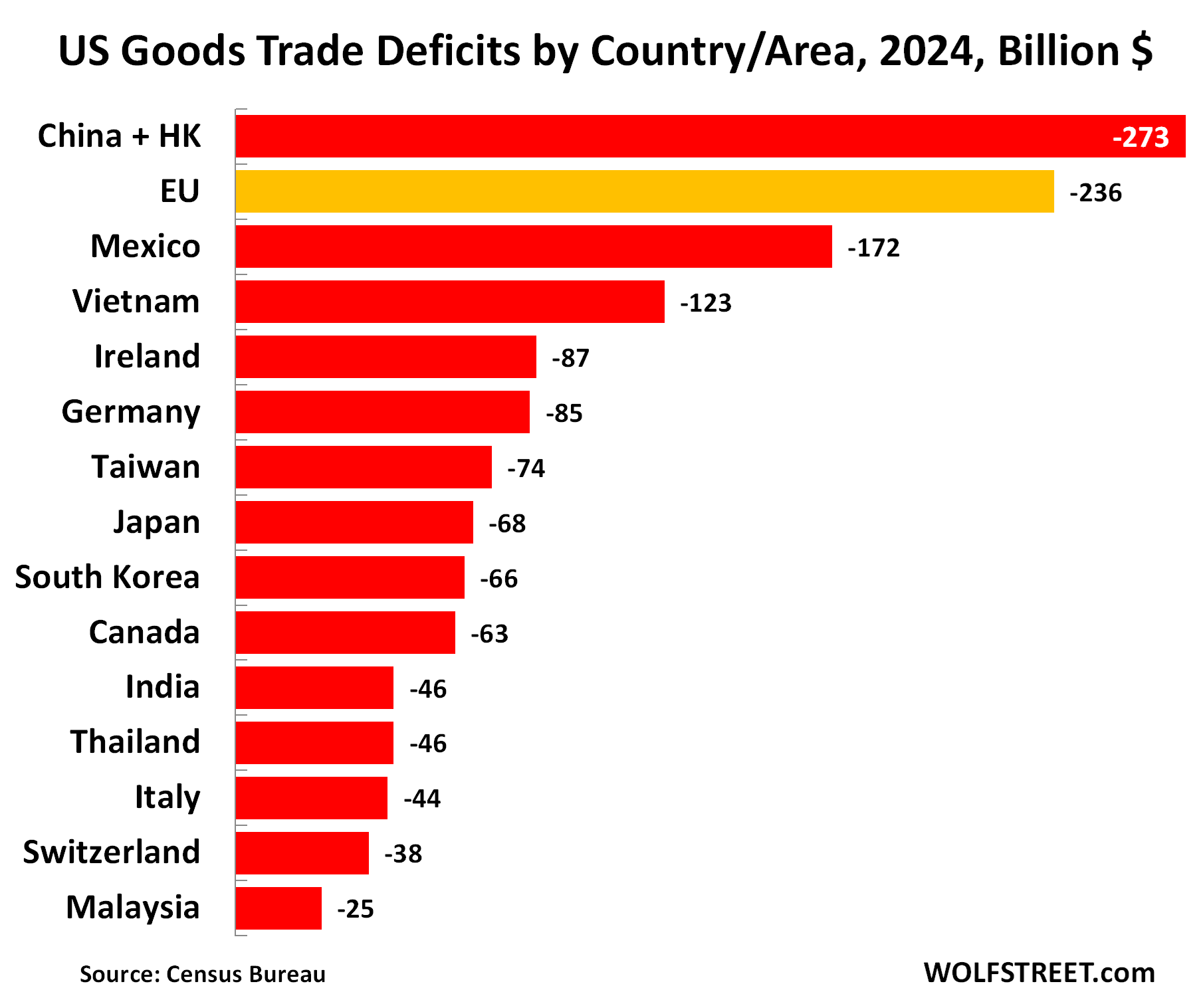

Some of the largest most profitable US companies pay little in corporate income taxes in the US because they manage to keep much of their profits outside the US, where they’re taxed in low-tax jurisdictions, such as Ireland. Apple is a great example of this – as we know from a 2013 US Senate investigation.

If Apple manufactured consumer electronics in the US, it could no longer shelter its income earned from those US sales, and would have to pay corporate income taxes on it in the US (or engineer another tax shelter). Tariffs level the playing field.

Trump specifically singled out Ireland on Liberation Day. The US had a larger trade deficit in goods with tiny Ireland ($87 billion in 2024) than with Germany ($85 billion).

This $17.4 billion in Customs and Excise Taxes was just the initial shot.

For mere mortals, it’s impossible to keep up with tariff chaos. Trump had imposed various tariffs before April 2, but on “Liberation Day,” he imposed additional tariffs, and later paused some of those additional tariffs for 90 days, while leaving the prior tariffs intact. Except with China, where he later raised the Liberation Day tariffs to 145%, after China counter-tariffed. But some China-made products have already been exempted from the additional 145% tariffs, such as smartphones. The governments of China and US are now sort of talking, or at least talking about talking. Numerous negotiations are apparently underway with corporate executives and with governments of other countries, each one trying to get their special deal. So whatever.

The “de minimis” exemption from all tariffs for shipments of $800 or less remained in effect throughout April and shippers didn’t pay any tariffs on them in April. But collections started in May.

That loophole accommodated an increasingly large flow of imports directly from China and other countries to US consumers and retailers. In the last fiscal year, 1.36 billion shipments came into the US tariff-free through that loophole, more than triple the number of shipments in 2018 (411 million shipments), according to Customs and Border Protection.

The stated dual purpose of tariffs is to first change the math for manufacturing in the US, and second, to increase tax revenues. Tariffs were the original tax revenues in the US, predating income taxes.

In terms of manufacturing in the US: There have already been numerous announcements of large investments in US manufacturing facilities by manufacturers across the board. These investments will take time to play out – years of big investments in the US before mass production can start. These investments alone are a big boost for the US economy. And companies such as GM that already have plants in the US have started to shift more production from their foreign plants to the US plants.

Other countries use far higher tariffs. India charges up to 110% on imported cars. China charges enough so that it’s not possible to sell mass-produced imported lower-priced cars in China. If you want to sell mass-produces cars in those countries, you have to make them there. And it worked for them, without a lot of moaning and groaning from GM, Tesla, Ford, etc.

Manufacturing in the US – and the investment, know-how, infrastructure, etc. that come with it – is immensely valuable to the US economy, including for its secondary and tertiary benefits, and also for the large amounts in federal, state, and local tax receipts these activities generate.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

Energy News Beat