By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

The underlying dynamics of the labor market bounced back in October, according to the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) from the Bureau of Labor Statistics today. The data continues to be muddled by the Boeing strike that lasted through October and ended in early November, and by three hurricanes – Francine in early September, Helene in late September through early October, and Milton in mid-October – whose heavy rains and flooding temporarily shut down work sites in a substantial part of the country.

As we saw a month ago, the Boeing strike and the hurricanes had substantially reduced payroll gains in October, as reported on November 1. The jobs report for November, to be released on Friday, will likely show a solid bounce-back from those weak gains.

But today’s JOLTS data is for October still, which is why the bounce during what was a rough October is particularly interesting, and speaks of a retightening labor market.

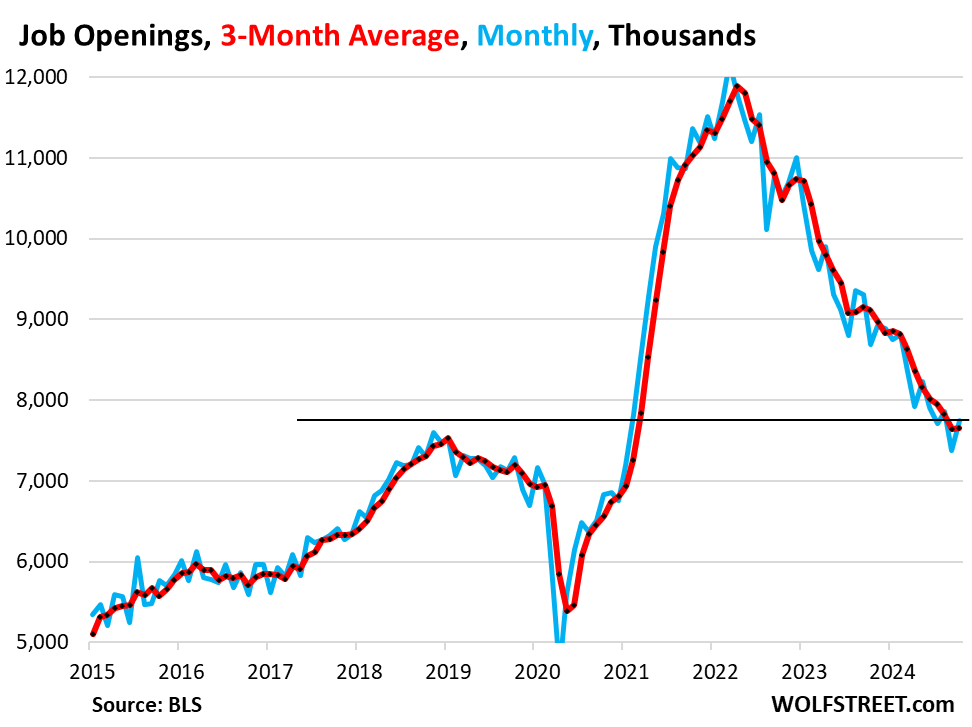

- Job openings spiked in October by the most since August 2023, after the drop in September, and are above where they’d been in July, and above the prepandemic record.

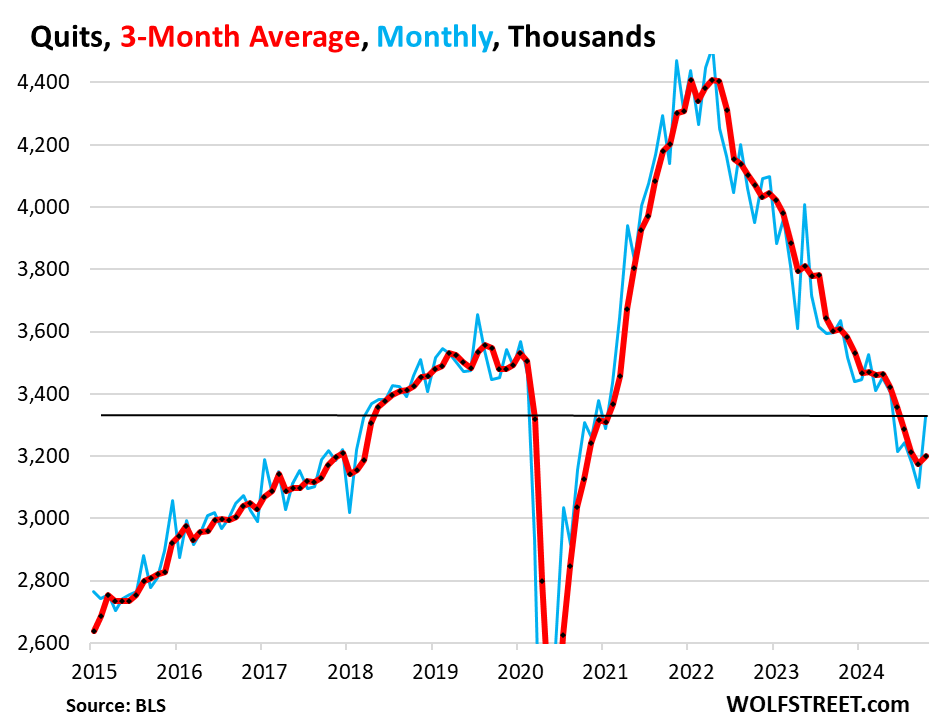

- Quits spiked by the most since May 2023, to the highest level since May 2024.

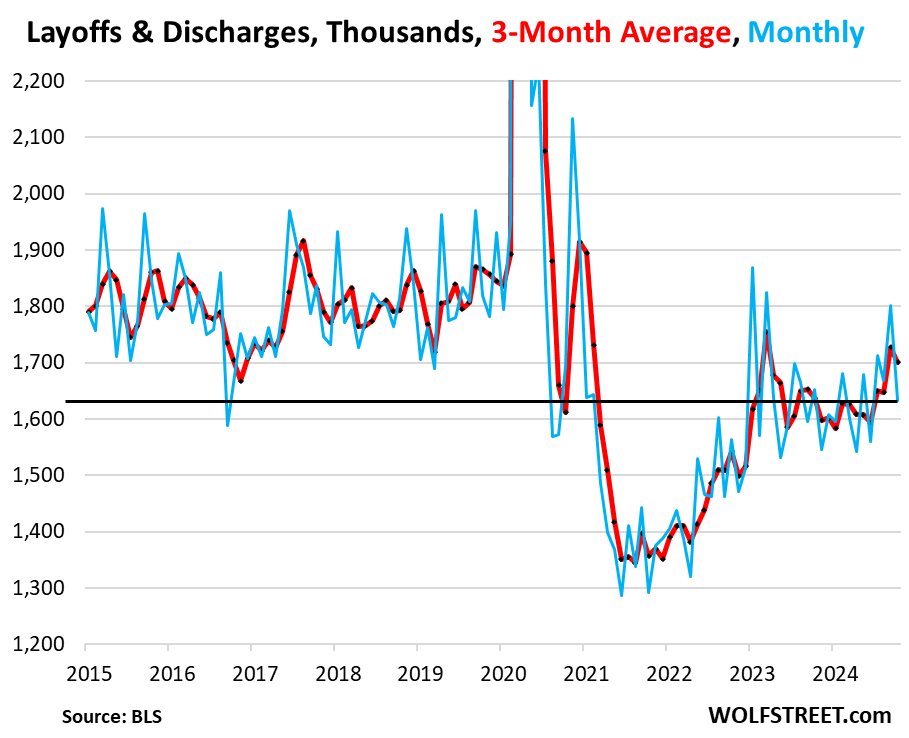

- Layoffs and discharges plunged by the most since April 2023, to the lowest since June.

- Hiring fell in October after the increases in the prior three months.

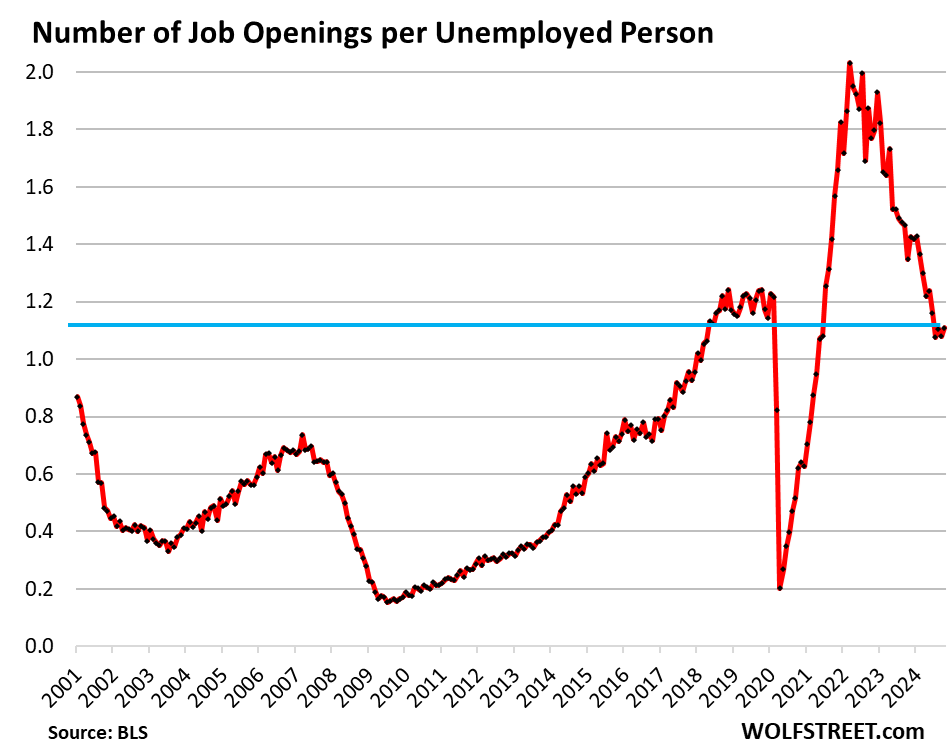

- The number of job openings per unemployed persons rose to the highest since June.

The Fed has already started backpedaling from the pace and depth of the rate cuts envisioned after its monster rate cut in September, which was triggered by what we now know was a false alarm about the labor market. And this data here will provide more reasons to continue backpedaling, and Powell will cite a few of the moves here at the FOMC’s post-meeting press conference on December 18.

Job openings spiked by 372,000 in October from September, seasonally adjusted, the biggest jump since August 2023, to 7.74 million, above where they’d been in July, above the prepandemic record (blue in the chart).

Not seasonally adjusted, job openings spiked by 928,000 to 8.17 million openings.

The massive churn of the labor force in 2021 and 2022 clearly has ended as fewer people are quitting, therefore leaving behind fewer job openings to re-fill, and fewer people to higher to re-fill those openings. But October was a sudden and big U-turn that points at increased demand for labor.

The three-month average, which irons out the month-to-month squiggles and includes revisions, ticked up to 7.66 million job openings, above the prepandemic highs in late 2018 and early 2019 (red):

The number of job openings per unemployed person – a metric of labor-market heat that Powell cites a lot – ticked up to 1.1 openings per unemployed person, the highest since June. This means that there are still slightly more job openings (7.74 million) than unemployed people looking for work (6.98 million).

The ratio has been roughly stable for five months, at a lower level than it had been during the hot labor market in late 2018 through February 2020. The sharp decline of this ratio until June was one of the reasons Powell cited specifically for the 50 basis-point cut; the metric was a sign that enough heat had come out of the labor market and that the Fed didn’t want it to cool further.

Voluntary quits spiked by 228,000 in October from September, the biggest jump since May 2023, to 3.33 million, the highest level of quits since May. The three-month average ticked up to 3.20 million.

The massive churn in the workforce during the pandemic, when workers jumped jobs and industries to improve their pay and working conditions, and to better match their skills and aspirations, had triggered the biggest pay increases in decades.

Fewer voluntary quits mean fewer newly open roles that have to be filled, so fewer job openings, and fewer hires to fill those openings. For employers, lower quits is good. It reduces the churn. Productivity rises when workers stay longer and learn the ropes. In addition, pay increases have moderated because employers no longer have to entice workers with aggressive pay packages to stay, or to come work for them.

But October’s surge in quits, if it is sustained, would be the first sign that workers are regaining confidence in the labor market, that more of them are getting hired away from their current job by more aggressive employers, and that the grass looks greener on the other side of the fence once again. These would be hallmarks of a re-heating labor market.

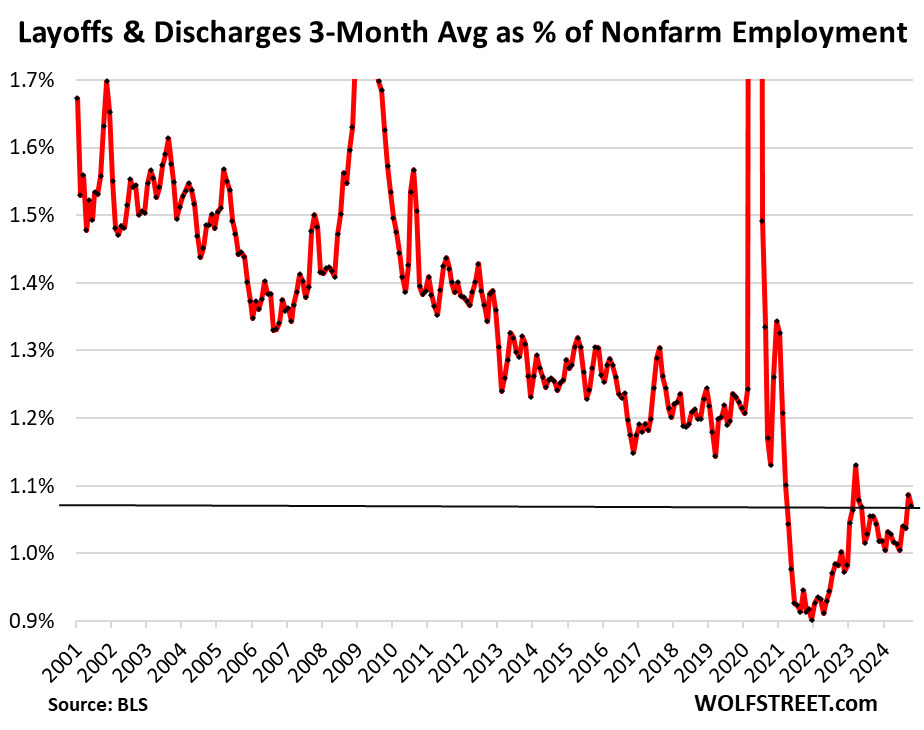

Layoffs and discharges dropped by 169,000 in October from September, the biggest drop since April 2023, to 1.63 million, the lowest level since June. The three-month average fell to 1.70 million.

Layoffs and involuntary discharges include people getting fired for cause. Getting fired is a standard feature in America, and it occurs a lot even during the best times. And currently, they’re still historically low.

Layoffs and discharges as percentage of nonfarm payrolls – which accounts for growing employment over the years – declined to 1.03%. The three-month average declined to 1.07%, both far below any time during the pre-pandemic years in the JOLTS data going back to 2001. It documents that employers are hanging on to their workers.

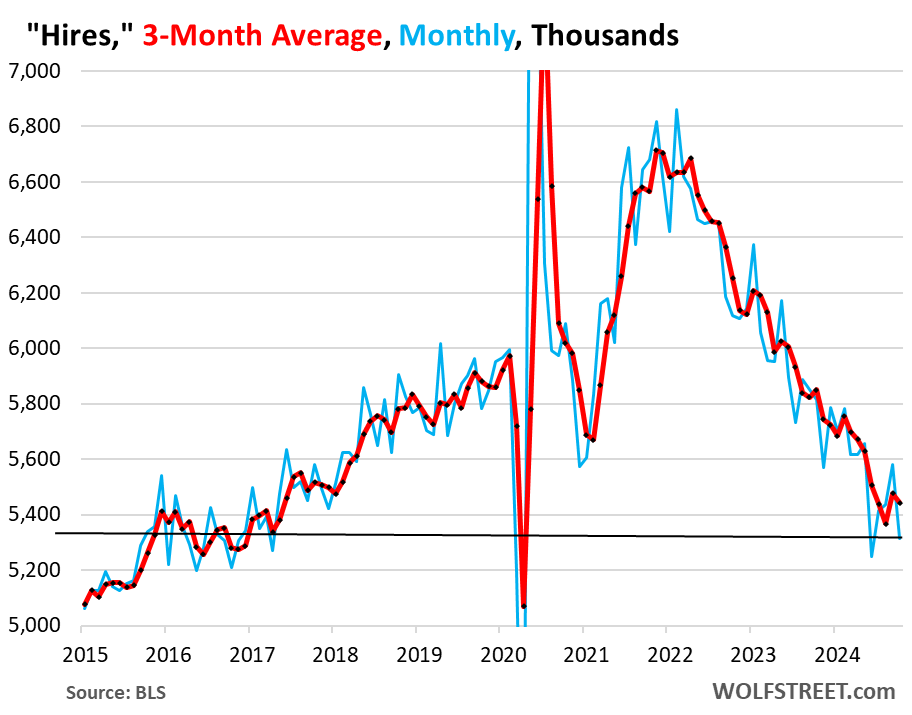

Hires dropped by 269,000 in October from September, seasonally adjusted, after three months in a row of increases, to 5.31 million.

Not seasonally adjusted, hires rose by 104,000 to 5.73 million.

The three-month average dipped to 5.44 million hires (red).

These workers were hired to fill roles left behind by workers who had quit or were discharged, and to fill newly created roles.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()

Energy News Beat