By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

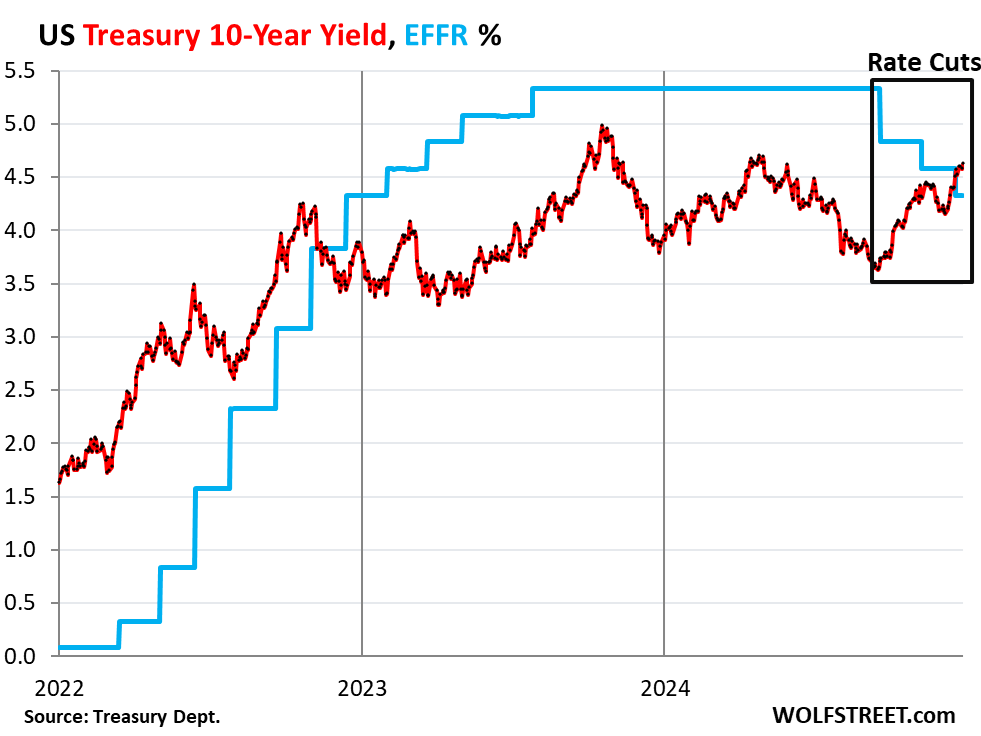

Treasury yields and the now un-inverted and nicely steepening Treasury yield curve passed another landmark on Friday, maybe the first such landmark ever: While the Fed cut its policy rates by a full percentage point, long-term yields have risen by a full percentage point.

Since September 16, the low point two days before the rate cut, the 5-year yield has risen by 106 basis points, the 7-year yield by 105 basis points, the 10-year yield by 100 basis points, and the average 30-year fixed mortgage rate by 100 basis points.

The 10-year Treasury yield reached 4.62% on Friday, the highest since May 1 (red), while the Effective Federal Funds Rate (EFFR), which the Fed targets with its policy rates, was 4.33% (blue). This equal move into opposite directions of the EFFR and the 10-year yield is amazing.

The yield curve steepened nicely after un-inverting entirely.

With longer-term Treasury yields rising, while short-term Treasury yields haven’t changed much during the week – no longer pricing in any rate cuts during their time window – the yield curve has steepened further, after it un-inverted entirely a week ago.

At the longer end, 5-year and 7-year yields rose by 8 basis points during the week, while 10-year and 30-year yields rose by 10 basis points, with the 30-year yield rising to 4.82%, the highest since April.

The chart below shows the yield curve of Treasury yields across the maturity spectrum, from 1 month to 30 years, on three key dates:

- Gold: July 25, 2024, before the labor market data spiraled down (which was a false alarm).

- Blue: September 16, 2024, the low point two days before the Fed’s initial cut.

- Red: Friday, December 27, 2024.

Even though the yield curve has gently steepened this week, it remains fairly flat, with only a 31-basis point spread between the 2-year yield (4.31%) and the 10-year yield (4.62%), but that spread has widened from 22 basis points a week ago.

In other words, investors are accepting still low term premiums. But when the yield curve was inverted until recently, longer-term yields were lower than short-term yields and the term premium was negative.

As the yield curve normalizes, it will steepen further and term premiums will rise. This could happen in two ways: With shorter-term yields falling or with long-term yields rising, or both.

Why the divergence of the 10-year yield from the EFFR?

Among the primary reasons the Fed cut its policy rates by 100 basis points, as it pointed out many times, were the loosening labor market conditions and the substantial cooling of inflation since mid-2022.

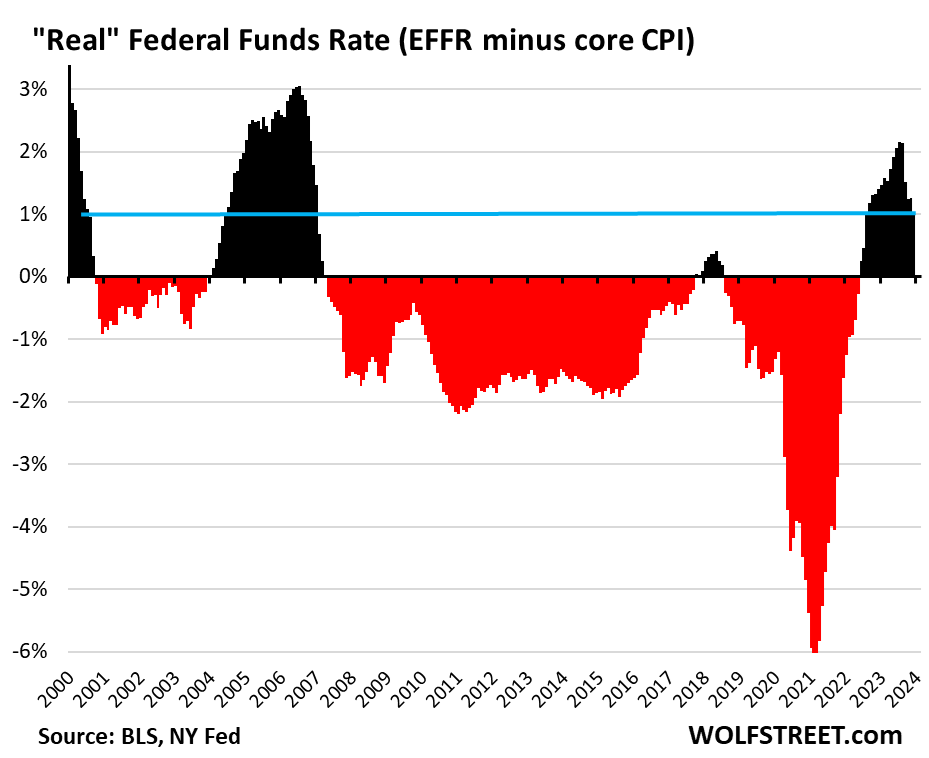

The labor market remains relatively solid, but it shouldn’t loosen further, the Fed said. And inflation has cooled from the highs in 2022, with all major inflation rates – CPI (2.7%), core CPI (3.3%), PCE price index (2.4%), and core PCE price index (2.8%) – well below the Fed’s policy rates and well below the EFFR (5.33% before the cuts, 4.33% currently).

With inflation rates higher than the EFFR, the “real” EFFR is positive (adjusted for inflation). Compared to November core CPI, the highest of the main inflation readings at 3.3%, the real EFFR currently is +1.0%. Since 2008, the real EFFR was mostly negative.

But the Fed didn’t cut because it saw a recession coming. Seeing a recession is the normal reason for cutting rates, but the economy has been growing at a pace that is substantially higher than the 15-year average, there is no recession in sight, and economic growth seems to have picked up in the second half, running above 3%.

The fact that the Fed has hiked rates so fast and so far, and has kept them there for so long, and that inflation has cooled so much, without the economy going into a tailspin, but cruising along at an above average pace, is historically unusual.

Faster economic growth often leads to higher longer-term yields. Conversely, recessions lead to low longer-term yields. Normally when the Fed starts cutting rates, it sees a recession, and longer-term yields are falling along with the Fed’s policy rates because the bond market too is seeing that recession.

But this time around, the Fed cut amid above-average economic growth with no recession in sight – so that’s unusual – and longer-term yields have risen amid this solid economic growth.

The bond market is getting a wee bit nervous.

Inflation concerns are now re-emerging. It has been warming up again in recent months. The Fed itself at the last meeting projected a scenario of higher inflation by the end of 2025 than now, and higher “longer-run” policy rates, and its reduced its projections for rate cuts from four to just two in 2025 for those reasons. Powell at the press conference said that the rate cut had been a “close call,” and doubts emerged during the press conference that there may even be two cuts next year.

And there are concerns that continued stimulative fiscal policies and additional tariffs will provide further fuel for inflation.

In addition, there are rising concerns in the bond market about the ballooning US debt, and about the flood of new supply of Treasury securities that the government will have to sell in order to fund the out-of-whack deficits. Treasury buyers and holders are spread far and wide, but higher yields may be necessary to reel in the mass of new buyers needed, even as the Fed is shedding its Treasury holdings through QT.

These are worrisome thoughts for potential buyers of long-term Treasury securities; they want to be compensated through higher yields for the risks of higher inflation and the risks this flood of new supply might bring.

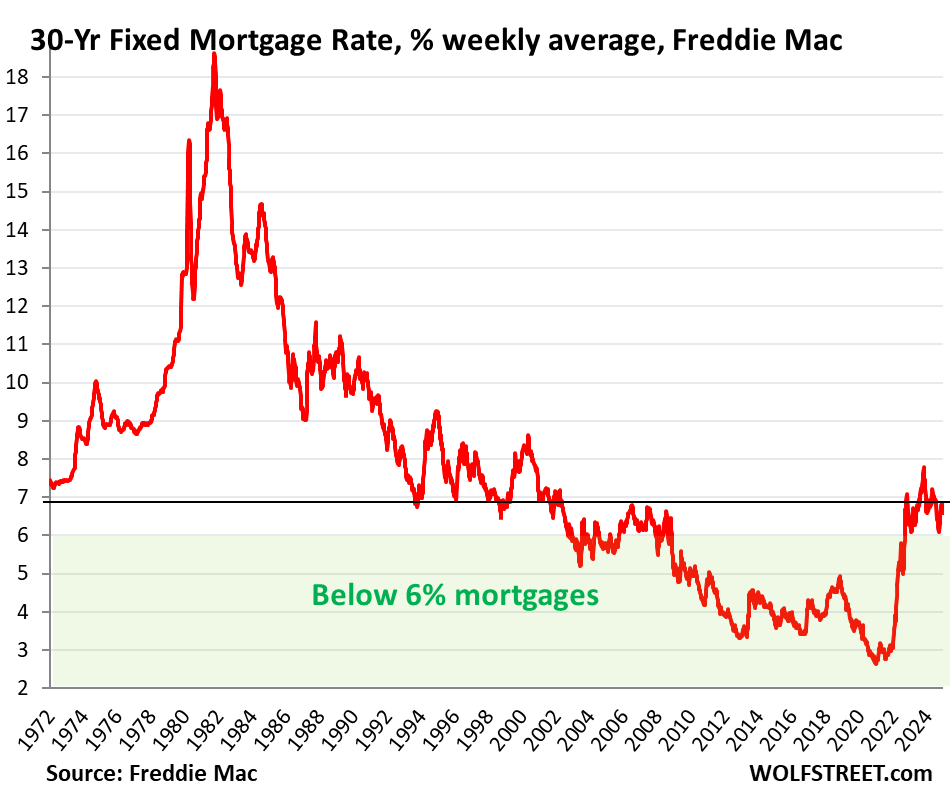

Mortgage rates back around 7%.

Since the rate cut in September, the average 30-year fixed mortgage rate has risen by 100 basis points, from 6.11% to 7.11% on Friday, according to the daily measure from Mortgage News Daily.

The weekly measure from Freddie Mac has risen by 77 basis points over this period, to 6.85%. These higher mortgage rates despite 100 basis points in rate cuts have driven the real estate industry up the wall.

But those 6%-plus mortgages were normal in the decades before 2008, even during times of rate cuts. It’s only after 2008, when the Fed’s QE and interest-rate repression distorted everything, that these low-rate mortgages began to mess up the housing market. So maybe it’s time to get re-used to these kinds of mortgage rates that were normal before 2008.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()

The post 10-Year Treasury Yield Rose 100 Basis Points since September as the Fed Cut 100 Basis Points. Why the Historic Divergence? appeared first on Energy News Beat.

Energy News Beat